Got a nice old bike in your garage? Maybe I can help you get it working again.

Monday, October 31, 2011

Sunday, October 23, 2011

Repacking Wheel Bearings

First you have to remove the cassette. You will need a cassette lockring tool and a chain whip.

Shove the lockring tool into the cassette and put a big wrench around it (the one shown is a 15/16" size, otherwise use a big adjustable wrench or a 1/2" drive breaker bar). Next push down on both tools to unscrew the lockring, this may need a lot of effort.

For freewheel hubs, insert the specific freewheel tool into the freewheel and wrench it off with lots of force, being careful not to let the tool slip. If you have a prong style remover, use the quick release skewer or axle nut to hold the tool tightly in place as you break the freewheel loose (Here's a quick tutorial to remove a freewheel).

Now slide off the cassette and place a cone wrench on the flat sides of the axle cone (the inner piece) and put an adjustable wrench tightly around the outer locknut:

Tuesday, October 18, 2011

Chains

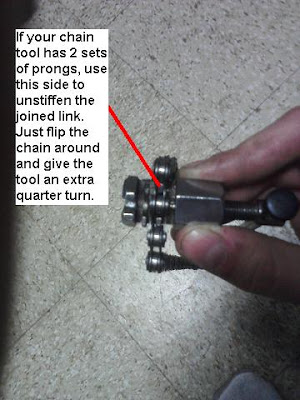

Shimano HG chains require using a special pin to reinstall the chain, so for these you would push the old pin all the way out and use the special pin to join the chain. Many newer chains come with removable master links, so the chain tool is only needed to shorten the chain for these.

Friday, October 14, 2011

Cantilever Brakes

To change or adjust the pads, hold brake arm in place with an allen wrench while unscrewing the nut on the opposite side with the right size wrench (adjustables don't work well here, use a box end wrench):

This will loosen up the clamp holding the pad in place, and you can now move it around or swap the pad out for a new one. Position the pad so that it lines up with the curve of the rim, and hits the rim squarely rather than on a sharp angle. You also want to angle the pads inward slightly to keep the pads from squealing, and to give the brake a softer feel.

Finally, hold the allen wrench in place while tightening the nut to lock in the pad's adjustment. Pull the brake lever and check to see where the pads meet the rim. The pads should be aligned with the rim, and the shouldn't drag when the brake lever is released. If one side is dragging, then use the spring tension adjustment screw to center the brake arms:

Turning this screw in will pull the brake arm away from the rim, while loosening it will move the brake closer to the rim. You want the brake pads to sit the same distance away from the rim, so adjust this screw accordingly. If the brakes are centered, slightly toed in, and have a strong feel then you're done.

Tuesday, October 11, 2011

General Notes

- Most bikes use metric bolts, so don’t use English wrenches. Old Schwinns are an exception.

- Keep your chain well oiled and your tires properly inflated. WD-40 is a degreaser and water displacer, not a chain oil.

- Don’t leave your bike outside if you can avoid it. Rain and morning dew will quickly ruin any steel parts (chain, gears, bearing surfaces, cables, etc.).

- Pedals are NOT self tightening, loose ones are self stripping.

- Dish soap is a great degreaser.

- Small bolts are easy to ruin with the wrong size wrench. Use a socket or box end wrench whenever possible.

- Most parts are held on by 1 or 2 bolts; make sure they’re tightened properly.

- Rubbing wet aluminum foil on slightly rusty chrome works wonders.

- Don’t use a hammer.

- Youtube is your friend.

- Higher quality bikes often use quick release levers to secure the wheels and/or seatpost. The lever screws into a nut, and then flips closed to put lots of pressure on the frame. For most quick releases, screw the lever into the nut until the lever can be closed with resistance starting at the halfway mark. The lever should not be too hard to fully close, nor too loose. Unscrewing the nut will make the lever easier to close, but reduce the clamping force. Tightening the nut does the opposite.

Monday, October 10, 2011

Wheelbuilding Tutorial

First you'll need a hub, rim, and spokes of the correct length. There is a spoke calculator spreadsheet online (spocalc) if you don’t know which spokes to use. I recommend building a complete practice wheel before making one that someone is actually going to ride on. Having another (new-ish) bike to estimate final spoke tension from is a big help. These are the basic steps. More detailed information is available on Sheldon Brown’s website.

- Check that all the spokes are the same length by standing them up on a flat surface, picking out any that are too tall or short. Slightly mismatched ones make life a little harder for you later on. If the hub has been previously used, try to follow the indentations near the spoke holes as you lace the wheel. Make sure the rim is straight by laying it on a flat surface. Minor imperfections can be bent back into shape.

- It is customary that rim labels are readable on the right hand side, and that the hub’s label should face the valve hole (not really necessary, just for looks). Important - Spoke holes are usually offset for each side of the hub, so a hole that’s closer to the left will be for a left side spoke.

- Start by dipping the spoke’s threads in grease. Vaseline works fine for me, you can also use linseed oil (recommended) or special spoke prep (stupidly overpriced). Now lace the first spoke through the hub, following any existing indentations. For example, if there is a notch on the outside of the flange, thread the spoke from the inside of that flange so that the spoke’s elbow will sit inside of that notch.

- The first spoke is most important. Start on the right hand side, lace a spoke through a hole in the hub from the outside in. Then connect this spoke to the rim by lacing it through the hole next to the valve hole. Screw a spoke nipple on top, leaving a few threads showing. Make sure that the hole on the rim is offset towards the side of the hub that you are working on.

- The rest of the spokes will be laced in 4 groups. Continue lacing the first group the same as the first spoke, skipping 1 hole on the hub flange and 3 holes on the rim. Make sure each spoke goes into the hub the same way. Once the entire group is laced, check for errors: there should be 3 empty holes (not counting the larger valve hole) on the rim between each spoke, and there should be an empty hole on the hub between every spoke. Each spoke should exit the hub on the inside of the flange.

- Now you can start lacing the second group. Thread a spoke from the inside of the hub outwards. The spoke should now exit the hub on the outside of the flange. This spoke will go in the opposite direction of the previous group, and will determine the crossing pattern. Most wheels are built with the spokes crossing over 3 other spokes. This is called 3 cross lacing. 4 cross is also somewhat common, as is radial lacing for the front wheel. Angle the new spoke so that it crosses over the correct number of spokes (if you don’t know then try 3 at first, if it is obviously too long and is sticking way out of the rim, try 4). The new spoke should be twisted around the last crossing spoke before entering the rim. This will create a more stable wheel. Connect it to the rim with a spoke nipple, skipping 1 hole between the existing spokes.

- Lace the remaining spokes in the second group following the same pattern: spoke exiting on the outside of the hub flange, opposite direction of the previous group. Make sure every new spoke is twisted over the last crossing spoke, and make sure there is an empty rim hole between each spoke now. Congratulations, you’re halfway done lacing.

- The third group should be laced from the outside inwards on the left side flange. You will have to bend the spoke around the existing spokes before connecting to the rim. This group will be built much like the first, angled in the same direction. Check that there is an empty flange hole between every new spoke, and that every 4th hole on the rim is empty.

- The last group will go in like the 2nd. Lace a spoke through the hub from the inside out, so that the spoke exits on the outside. This spoke will be angled opposite of the third group, but in the same direction as the second group. Remember to twist the spoke over the last crossing spoke before connecting to the rim. Check for errors once all the spokes are laced. Now comes the tricky part.

- Important - Turn every spoke nipple so that the threads are just barely hidden on each spoke. This is necessary for even tensioning.

- Starting at the valve hole, tighten each spoke 1 half turn (or 1 full turn if they’re still loose). After one complete round, continue tightening each spoke in ½ turn increments. Check the wheel for roundness; hopefully it is still relatively straight.

- Put the wheel on the bike (or a truing stand if you’re that fancy) and begin truing. This involves tightening and loosening spokes in bent areas in equal amounts (1/2 or ¼ turns for now) until the rim spins straight again. Use the brake pads to judge where the bent areas are. If the rim pulls to the left in one section, tighten the right side spokes in the bent area while loosening the left side spokes the same amount. Check any adjustments to make sure you didn’t overcompensate.

- Once the wheel is true (doesn’t have to be perfect yet), add another round of tension. The spokes should emit a moderately high pitch when plucked.

- Begin stress relieving by grabbing parallel spokes and squeezing hard (wear gloves). This stretches the spokes into a more natural shape and will prevent them from deforming as you ride. Stress relieving also prevents spokes from breaking later on (metal fatigue, physics, bla bla blaa). This is actually a very important step.

- Continue truing/tensioning/stress relieving until the spokes become somewhat difficult to turn. They should emit a moderately high pitch when plucked. If they have been correctly tensioned, then all the spokes on one side should have a similar pitch.

- Dishing: This step applies to rear wheels and front wheels with disc brakes. The wheel may be adequately tensioned and true, but the rim may not be centered within the frame. Dishing the rim involves loosening all the spokes on one side while tightening all the spokes on the other side in order to bring the rim towards the center. Start by tightening each drive side spoke (or disc brake side for front wheels with discs) by half a turn and loosen the spokes on the opposite side by ½ a turn. Continue this process until the rim appears centered. Check the dishing by flipping the wheel around in the frame. If the rim is still in the same place as it was before you flipped the wheel around, then it is dished properly.

- Finish tensioning the rim. It helps to have another properly built wheel to use as a reference for the amount of tension needed. Pluck the spokes on the other wheel, and tension your wheel until the spokes emit a similar tone. Keep in mind that the left side spokes on a rear wheel will have a lower tone than the right side due to dishing. Important note – as spokes become tighter they tend to twist about 1/8th to 1/4th of a turn. You will have to turn an extra 1/4th of a turn when increasing tension, and then loosen that 1/4th after making the adjustment. This keeps the spokes straight and the wheel true.

Wheel Repair

A wheel that suddenly starts wobbling usually means a spoke broke. Replacements can be threaded into the hub and into the existing spoke nipple. Pay attention to the wheel’s existing spoke pattern, and lace the spoke through the wheel the same way. Deflate the tire, then tighten the spoke nipple with a spoke wrench or flat screwdriver on top (remove the tire and rim strip first to use the screwdriver). Deflating the tire protects the inner tube from punctures as you turn the spoke nipple. Tighten the new spoke until the wheel spins true again. Finally, pull hard on the new spoke to stress relieve it.

Sometimes a wheel will just go out of true over bumps. A mildly warped rim can usually be corrected by increasing the tension on the spokes opposite of the bend, and decreasing the tension on the bent side. This will pull the rim back into a straight or “true” rotation. Tightening the spoke nipple increases spoke tension, loosening will reduce tension. In general you want all the spokes on one side of the wheel to have the same tension. This will result in the strongest and most stable wheel, but will not be possible with a well-used rim. In that case, do the best you can to get it straight again.

Here's some more information. Spokes are all in tension on a bike wheel. This tension distributes the rider’s weight across the entire wheel rather than just on the spokes between the axle and the ground. The rim itself is relatively weak, and needs considerable spoke tension to hold it in place. The spoke tension also needs to be balanced on each side of the wheel, otherwise the rim will wobble towards the side with more tension.

Sunday, October 9, 2011

Repacking Bearings

Hub Bearings:

- Wheel bearing work requires cone wrenches and adjustable wrenches. Put the right size cone wrench on the inside bearing cone, and an adjustable wrench on the outer locknut. Unscrew the locknut, using the cone wrench to keep the axle from turning.

- Next unscrew the cone wrench, placing the wheel over an old towel or rag to catch the dirty bearings. Remove the axle, and gently pry out the balls using a small flat screwdriver.

- Wipe all bearings clean, using degreaser when necessary (don’t use simple green on aluminum parts). When all surfaces (hub, balls, axle cones) are clean, fill each side of the hub with fresh grease.

- Place the ball bearings into the grease (typically 10 per side on the front, 9 per side in the back). Carefully place the axle back inside on the correct side, and then screw on the other hub cone. Replace the remaining washers and locknut, and then tighten the locknut against the cone. Adjust the bearings so that they spin smoothly and there is no play in the wheel.

Bottom Bracket Bearings:

The bottom bracket is the bearing assembly which allows the cranks to rotate.

- 3 piece bottom brackets require a crank puller (for cotterless cranks), lock ring tool, and a large adjustable wrench. First remove the cranks by unscrewing the crank bolts, then screwing the crank puller all the way into the crank and turning the lever until it pops off.

- For very old cranks with cotter pins, unscrew the nut holding the cotter on a little bit, then use a vice or large C clamp to press the pin out from the threaded side. You will need a brace for the other side of the pin (a block of wood with a hole drilled for the pin should work, or a 3/8” socket that’s bigger than the nut).

- Remove the lock ring on the left side cup, then unscrew the cup. This is threaded normally. Remove the spindle and then unscrew the drive side cup using the 2 wrench flats. This piece is reverse threaded, and may require considerable force to remove (the right side cup can remain in place if removal is difficult; just clean it from the inside of the frame).

- Clean all ball bearings along with the cups and spindle. Clean out the threads in the frame if necessary.

- Repack the drive side cup with lots of grease and pack it full of ball bearings (there should be 11 per side, 1/4” size). Grease the threads on the cup and screw it back into the frame.

- Pack the left side cup with grease and ball bearings, and then reinsert the spindle into the shell. Carefully screw the left side cup around the spindle to avoid disturbing the ball bearings.

- Leave some play in the left cup. Tighten down the right side cup hard once the spindle and bearings are secure. Finish screwing the left cup in.

- Secure the bearing adjustment with the lock ring. There should be no binding nor play in the spindle. A minor amount of drag is acceptable.

- Bolt the cranks back on with lots of force on the crank bolts. If using cottered cranks, use the vice to drive the pins back in, and screw the nuts back on. The nuts will only hold the pins in place, not tighten the pins.

- Older bikes typically have threaded headsets. This is the bearing assembly that allows your handlebars to rotate. First remove the stem and the top nut, as well as any spacers, washers, or brake cable stops.

- Unscrew the top bearing race over an old towel so that the bearings can’t get lost as they fall out. Once the race is unscrewed, carefully slide out the fork (the front brake cable may have to be disconnected).

- Clean all bearing surfaces, and put any loose ball bearings back into their retainers. Pack the top and bottom frame cups with grease, and replace the ball retainers.

- Slide the fork back in, then screw on the top race. If your headset chronically loosens, adding blue loctite on the fork’s threads may help.

- Replace all washers in the original order and screw on the top nut. Adjust the bearing race for minimal play, and then tighten the nut. Check for tightness/play, and adjust accordingly.

- Replace the stem and reconnect the brake.

- Threadless headsets use a clamp on stem rather then a threaded locknut to secure the headset. This system is more secure and easier to service.

- First unbolt the top cap, and then unscrew the bolts holding the stem to the fork.

- Remove any spacers and slide the fork out. The bearing surfaces themselves are similar to the threaded headsets, so clean them and repack with grease.

- Carefully replace the fork once the bearings are secure, then add the spacers and stem. Screw on the top cap.

- The top cap controls the preload on the bearings. It does not need to be tightened very hard and it isn’t a structural part of the bike once the stem bolts are tightened. Simply screw in the top cap until play is eliminated, then align the stem and tighten down the stem bolts.

Bearing Adjustment

Wheel bearings should spin freely with very little or no drag. If you take the wheel off your bike and cannot easily spin the axle with your fingers, then the bearing is too tight. Adjustments require a special tool called a cone wrench (typically 13mm for front wheels, 15mm for rear). Using a cone wrench on both sides can quickly loosen a tight bearing. Putting an adjustable wrench on each outer locknut can quickly tighten a loose bearing (except for old hubs with keyed washers behind the locknuts, for these you use the cone wrench and an adjustable on the same side). Quick release axles should have a very tiny amount of play with the wheel off, since the skewer compresses the bearings.

Older 3 piece cranks: If your cranks are wobbly you may be able to tighten the bottom bracket bearings without removing the cranks. Loosen the lock ring on the left side of the bottom bracket, then carefully screw in the adjustable cup until the play is gone. Retighten the lock ring while holding the adjustable cup with a thin wrench.

If the cranks continue to loosen up, the right side cup is probably loose. To fix this remove both crank bolts, then the cranks arms with a crank arm puller (no, a hammer doesn’t work). Loosen the adjustable (left side) cup a lot first, then put a big wrench on the right side cup. For French or Italian frames turn clockwise. Most other frames are reverse threaded here, so turn counterclockwise to tighten. Use plenty of force. Finally screw the left side cup back in until play disappears, and secure the adjustment with the lock ring. Bolt the cranks back on again, using lots of force on the bolts.

One piece cranks (old Schwinns, newer cheap bikes): The bearing is held tight by a nut on the left side. This is reverse threaded, so turn clockwise to loosen. Adjustments can be made to the bearing cone behind the lock nut and keyed washer, turn this counterclockwise to remove play. Tightening the lock nut will increase pressure on the bearings here, so make sure they do not feel rough after tightening.

Headset bearings: If your steering feels clunky there is probably play in the headset. On older bikes this is secured by a large nut on top of a large bearing cone. Loosen the top nut, and then screw in the bearing cone under the nut to remove play. Retighten the top nut while holding the bearing cone in place in order to lock in the adjustment. Make sure the handlebars still turn freely.

In general you want the ball bearings to spin freely. You don't want to feel play, nor excessive grittiness. Loose or tight bearings both wear out faster than properly adjusted ones.

Thursday, October 6, 2011

Shifting Adjustment

- The rear derailleur’s limit screws must be adjusted properly. These screws will stop the derailleur from moving too far past the gear cluster. They're usually located either on the front of the derailleur or on the left side. The low limit stop (usually marked L) is the most critical. This screw should allow the chain to engage the biggest rear cog, but NOT shift past it into the spokes. The rear derailleur’s upper pulley should be centered directly underneath the biggest gear when it hits the L limit screw. Similarly, the high limit screw (H) should not restrict the chain from moving to the smallest rear cog, but shouldn't let the chain move past it.

- The front derailleur should not rub the chain. The barrel adjuster on the shifter controls the derailleur’s position for the middle gear (if your bike has straight handlebars). The front derailleur's position in the small gear is controlled by the low limit screw (L), and the high gear position is controlled by the high (H) limit screw. Improper limit screw adjustment can throw the chain off the sprockets, so be careful.

- Indexing adjustment: Generally, the rear derailleur’s upper pulley should be positioned right below the selected gear. Use the barrel adjuster to adjust hesitant shifting in ¼ turn increments. Screwing it inwards (clockwise) makes it easier to upshift, unscrewing it (counterclockwise) makes it easier to downshift. These adjustments are sensitive so test the shifting after each quarter turn.

If the derailleurs are properly set up but the shifting is still hesitant, a sticky cable is usually to blame. Slide out the cable housings, clean the inner wire, then oil it before sliding the housings back in place. On newer bikes you can usually slacken the cable, then unhook the housings from the metal cable stops on the frame to clean the inner wire. On older bikes with closed cable stops you have to disconnect the shift cable. Frayed or kinked cables will also cause shifting problems. Comment with any specific questions, since every bike's situation is unique.

Shifting Technique

It seems like a lot of people buy multispeed bikes, but don't really know how to use the drivetrains. Or perhaps their gears are so out of alignment that the only safe combination is the small front ring/small back cog. Well, changing gear on a bike is much easier than on a motorcycle or stick shift car, and good technique makes riding much more enjoyable. Here are the basics:

- You usually don't want to pedal too fast or too slow. You can use your gears to find the perfect pedalling speed.

- The right hand shifter controls the back gear cluster. These are closely spaced gears for fine tuning your speed.

- The left hand shifts the chain across the front chainrings. The bigger front rings make it harder to pedal (but let you go faster), and the smaller rings make it easier to get up a hill. The gears in the back work the opposite (bigger back gears are easier, smaller back gears are harder).

How to shift:

- You need to turn the pedals while shifting in order for the chain to move. However you cannot shift smoothly if you put force on the pedals, so ease up until the chain is completely engaged.

- On an indexed system (newer bikes with clicks in the shifters) you only need to move the shifter to the gear you want. If the system is adjusted correctly, the chain should engage the selected gear very quickly.

- On a friction system (no clicks, found on old bikes) you need to guess where the gears are. This takes some practice, but you'll know when you're in gear when there are no rubbing sounds.

More tips:

- If you have to stop, it helps to shift to an easier gear beforehand so you don't have to awkwardly pedal slowly in a high gear. It's also important to shift before a steep hill, since you usually won't be able to shift while you're going up.

- As you start moving faster you should upshift to a harder gear so that you don't have to spin the pedals ridiculously fast.

That's really it, there's nothing hard about changing gear. Using the right gear will prolong the life of your drivetrain, and you can get many thousands of miles out of your parts if you spread the wear evenly across your gears.

Wednesday, October 5, 2011

Brakes

- When changing pads, make sure that the new pads are aligned with the rim’s curve, and they are centered on the rim. Don’t let them touch the tire, they’ll rip it to shreds. Make sure the pad’s bolts are nice and tight, or else they will move out of position and cause problems.

- Frayed brake cables MUST be replaced (broken cable = no brakes). The new cable should be oiled before installing through the housings.

- Usually the brake has a barrel adjuster to help you dial in the lever movement. Unscrew the barrel to move the pads closer to the rim, and screw it in to pull the pads farther away.

- Cable Installation: Pull the cable tight, and hold the brakes close to the rim while tightening the cable anchor bolt. Use the barrel adjuster to bring the pads a desirable distance to the rim.

- Sticky cables can sometimes be revived by dripping light oil into the cable housings. You’ll have better results, however, if you unbolt the sticky cable from the brake and remove it from the housings. Wipe down the cable until it’s clean, then spray degreaser or WD-40 into the housings to flush out dirt. Rinse the degreaser out of the housing, oil the cable and housing, and reinstall.

Bike Tools

- Bike Pump - A small electric one is a decadent luxury, otherwise a floor pump with a psi gauge is good enough.

- Tire Levers - I used to use screwdrivers and somehow never popped a tube. Then after I got the levers I popped a tube with a screwdriver (don't use screwdrivers).

- Chain Lube - A $3 quart of motor oil will last years. Commercial chain lube keeps your chain cleaner though.

- 14 or 15mm wrench - For your axle nuts (if your bike isn't quick release). An adjustable works fine too if you know how to use it (make the jaws grip as tight as possible, and re-tighten after every turn).

There are more specialized tools that are necessary for advanced repairs. If you have a newer bike you'll probably never need these, but an older bike might have wobbly wheels, or loose bearings. These are easily fixed with the right tools. Good special tools include:

- Spoke Wrenches - These are almost a must have. I like the individual Park Tool versions. Use these to straighten wheels by tightening the spokes opposite of the wobble, You can also loosen the spokes on the same side of the wobble if the other side is tight. You can also build wheels from scratch with these.

- Cone Wrenches - These are necessary for repacking wheel bearings and properly adjusting them afterward. A pair of 13/14/15/16mm combination ones are sufficient for 99% of hubs.

- Cassette/Freewheel Remover - These are specific to your bike. All Shimano and Sram cassettes use the same cassette tool. Freewheels (the older gear cluster style) use a vast number of different tools. You'll need to remove the gear cluster to replace broken drive-side spokes, or repack the rear wheel bearings.

- Chain Whip - Used to hold a cassette in place for removal, or to remove a fixed gear cog. You can make one yourself with a 3/16ths" thick steel bar and a length of old chain.

- Crank Puller - Used to remove square taper or splined cranks from the bottom bracket spindle.

- Bottom Bracket Tools - There is a large splined socket used to install or remove a cartridge bottom bracket. Adjustable bottom brackets typically need a large adjustable wrench and a lockring tool. Outboard bearing bottom bracket cups use a very large wrench with round "toothed" jaws.

- Headset wrench - Not entirely necessary for threaded headset adjustment, but makes things a lot easier. I typically use a vice grip with a towel between the jaws and the cup to hold it in place since I don't even have one.

- Allen wrenches - Typically you will need 4, 5, and 6mm versions on newer bike parts. An 8mm Allen socket is useful for certain crank bolts.

- Chain Tool - This is necessary for installing or removing most chains. Even on chains with a master link, you will still need this tool to cut it down to the right size.

- Big Adjustable Wrench - This is a must-have if you intend to remove bottom brackets or headsets. A 12" or larger should suffice.

That about covers the tools needed for most bike work. Certain repairs are best left to a shop, such as headset cup installation or derailleur hanger alignment, since the tools needed are very expensive. I will post in-depth tutorials for more advanced repairs later on.

Friday Bike Adventure

Well we set sail for Daley Plaza around 5:30 after waiting for a brief storm to clear up. We miss the start by a long time, and while riding on wet city streets my Loyola friend gets a piece of glass in the front tire. I didn't bring a patch kit or tube, so we decide to press onward on a slowly leaking tire to try to find someone with a kit. After pumping it up, riding a mile or 2, pumping it some more, we actually catch the critical mass lunatics. Someone gives us a patch kit, and all is well in the world. Except that the glue is all dried up...

A few days later the Perspective section of the Chicago Tribune featured a half page article describing critical mass as state supported domestic terrorism. I didn't read the whole thing, but it's kinda funny how worked up people can get when they gotta wait in their climate controlled cars for an extra 15 minutes.

Tuesday, October 4, 2011

Patching Tubes

There are several different types of punctures, and knowing how they happen can help you avoid at least some of them. These are the most common kinds:

- Debris Puncture - Not much you can do about these other than avoiding the very edge of the road where glass, thorns, and metal shards tend to collect. You can usually see these sticking through the inside of the tire, and these will create small holes in the middle of the tube on the outside. These are the most common, and easiest to patch.

- Pinch Flat - These usually happen when you hit a hard bump without enough air in the tire. The rim itself will cut the tube on the inside of the tire, and there will usually be two small holes or slits in the tube near the rim's edge. These are common for dumb mountain bikers like me who ignore the minimum pressure on the tire's sidewall. Usually you'll need two patches to fix the tube.

- Valve Tear - This happens when you install the tube with the valve sticking out at an angle and inflate to full pressure. The tube tends to tear at the base of the valve, and this is not patchable. Make sure your valve stems are straight.

- Rim Strip Puncture - Sometimes you might see a single hole on the rim side of the tube. This happens when the rim strip or tape moves around and exposes one of the spoke holes. The tube will try to fill up the uncovered hole in the rim and then burst. This can also happen if the bare spokes are poking through the rim strip. For this case you must fill up the area around the spoke(s) before adding the rim strip. I usually make a small ball of duct tape and stick it on the spoke under the rim strip to protect the tube. In any case I recommend using adhesive cloth tape since it won't shift around as easily as a rubber strip.

- Mystery Puncture - This happens when you can't find anything in the tire and the rim strip is fine. Sometimes it's a defective tube, other times its a tiny steel wire embedded in the tire (a cotton ball will snag on this). Or it could be a previous patch that opened up.

In any case good luck, and hopefully you don't have to actually use any of this advice. Remember that the glue in those little bottles dries up after you open them, so a glueless patch kit (Park Tool brand works well) may be the way to go on the road.

Monday, October 3, 2011

New Blog

- Don't buy an old bike off craigslist unless you're prepared to strip it to a bare frame and regrease/adjust/replace everything.

- That guy who's selling you that vintage road bike for $200 pulled it out of a scrap heap last week and did absolutely nothing but take pictures of it.

- If the bike you're buying has a flat tire, expect to replace that tire, tube and rim strip. The moment you put air in it the tire will rip apart, guaranteed.

- The wheel, headset, bottom bracket, and pedal bearings have 30 year old dried up grease in them, and they'll self destruct after a couple hundred miles without fresh oil or grease.

Anyway I'll try to help you fix those nice old road bikes and keep them in service. With some care they can be just as nice to ride as a new bike, and they have much more character and cost much less. Here are some basic tips for now:

- Oil everything. Anything that moves, rotates, absolutely anything at all. Motor oil dissolves old grease and dirt very well, and can protect the bearings until you repack them with grease later on.

- Inspect the cables. Replace frayed or rusted ones. Dirty cables can usually just be cleaned, oiled, and reinstalled as long as they're intact. The shifting and braking will get much smoother with clean cables.

- Very old tires usually need replacement, especially if they're dry rotted or have bare threads showing.

- Rusty chains tend to snap. Consider replacing if the links are stiff.

These are the simple things to get an old neglected bike running again. There are many things you can do to further improve them, which I can post later. I am always open to requests on how to solve any specific problem.